“Getty v. Stability AI” — Why This Case Proves We Need a New Copyright for the Age of Artificial Creation

“Getty v. Stability AI” — Why This Case Proves We Need a New Copyright for the Age of Artificial Creation

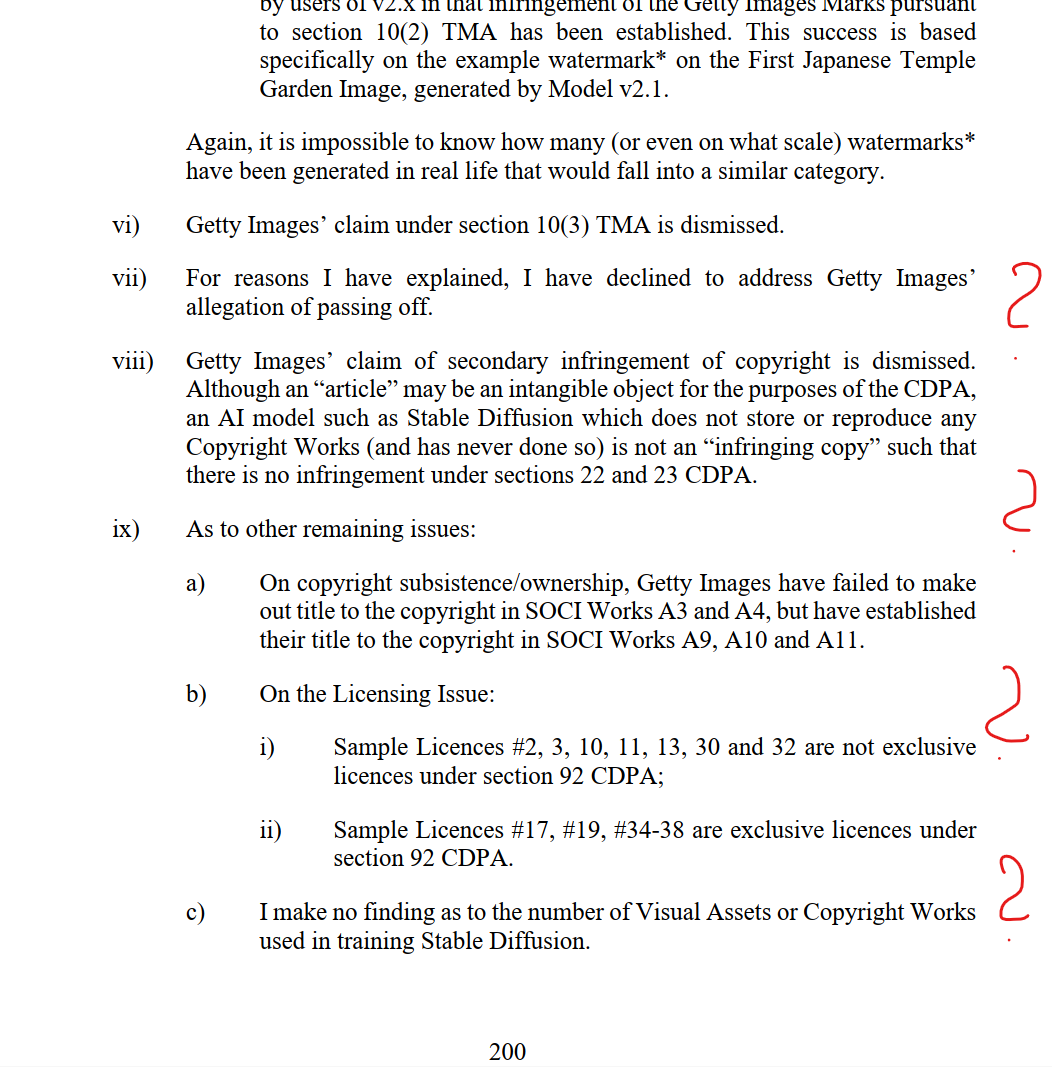

When the High Court of England and Wales published its judgment in Getty Images v. Stability AI yesterday, the creative world held its breath.

The Court found that training a generative AI model on vast datasets does not automatically constitute copyright infringement, as long as the model does not reproduce or “store” the works in a recognisable form.

One also could say: „If the copy is invisible, it isn’t a copy.“

(Though one might say the judge looked at the evidence with half-closed eyes. Even with “blurred” Getty watermarks, the use of copyrighted material was obvious — so obvious that trademark infringement was eventually acknowledged – because of the Getty-Logo.)

But — as in Kneschke v. LAION in Germany last year — courts still fail to grasp that AI does not work like a database. Its output is “remembered” and can be reproduced to such an extent that it becomes an exact copy.

Why should that be privileged simply because the machine remembered it instead of retrieving it?

The TDM exception allows mining if only the syntactic part is used — but AI mines the semantic part as well.

The judge assumed that AI-created images are not obviously the same as the originals. But the system itself was never built for this. Copyright law evolved to protect human originality and to mediate between creation and commerce. It presumes that authors create works, that they can be copied (if licensed), and that we can recognise when they are.

Generative AI breaks each of these assumptions — elegantly and irreversibly.

My doctoral research (AI and Authorship Redefined: Towards a Global Copyright Framework for Commerce and Human Originality) argues that we must stop treating AI merely as a tool and start seeing it as a syntactic system that learns semantics and imitates them.

Now via AI originality can be copied and multiplied. Everything AI produces must have an originator. And it is never the other way round.

Yet current doctrines protect only the semantic — the human, meaningful — side of creation, while the law – or should I say the judges – demands a recognisable copy before it calls it infringement.

AI collapses the line between syntax and semantics — and any definition that treats training data merely as “text and data mining” no longer fits this reality.

Unless lawmakers adapt to these new technical realities, copyright owners will keep losing ground.

Getty v. Stability AI is not the end of copyright.

It is the moment the law must evolve — from defending “the visible copy” to recognising the invisible structure of creation.

Human originality remains the source of value in this new creative economy.

But unless we redefine what a “work” is, we risk protecting only the past — not the act of creation itself.

hashtagAI hashtagcopyright hashtagauthorship hashtaginnovation hashtaghumanoriginality hashtagstabilityAI hashtagGettyImages hashtagAIlaw hashtagethics hashtagcreativity hashtaglaw